![]()

Ashes, Worms, and the

Compost Pile

Forty Days of Lent, Forty Years of Gardening

by Tessa Bielecki

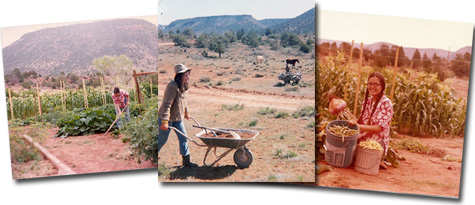

Tessa gardening in Sedona, Arizona, 1968

The liturgical season of Lent and the natural season of spring arrive close to one another each year. This is felicitous, because what we strive for in Lent is perfectly mirrored in our springtime activities. The very word “Lent” is even derived from an old English word which means “spring,” or more literally, “lengthening of days.”

Here is Nancy Woods’ description of one Pueblo Indian’s celebration of spring. Notice how his elemental ode to this season reflects the spirit of Lent.

When the hand of winter gives up its grip to the sun

And the river’s hard ice becomes the tongue to spring

I must go into the earth itself

To know the source from which I came.

Where there is a history of leaves

I lie face down upon the land.

I smell the rich wet earth

Trembling to allow the birth

Of what is innocent and green.

My fingers touch the yielding earth

Knowing that it contains

All previous births and deaths.

I listen to a cry of whispers

Concerning the awakening earth

In possession of itself.

With a branch between my teeth

I feel the growth of trees

Flowing with life born of ancient death.

I cover myself with earth

So that I may know while still alive

How sweet is the season of my time.

In an exquisite entry in Touch the Earth, a volume of American Indian wisdom, Chief Luther-Standing-Bear outlines the Dakota Indian’s love of the earth:

The old people literally loved the soil. When they sat or reclined on the ground, they had a feeling of being close to a mothering power. It was good for the skin to touch the earth, and the old people liked to remove their moccasins and walk with bare feet on the sacred earth. Their teepees were built upon the earth, and their altars were made of earth. The birds that flew in the air came to rest upon the earth, and it was the final abiding place of all things that lived and grew. The soil was soothing, strengthening, cleansing and healing. That’s why the old Indians still sit upon the earth instead of propping themselves up and away from its life-giving forces. For them to sit or lie upon the ground is to be able to think more deeply, to feel more keenly, to see more clearly into the mysteries of life.

Christian Earthiness

Native American spirituality is characteristically

earthy. So is our own Judeo-Christian heritage.

Unfortunately we have forgotten. Or perhaps

we never knew it because we have lost touch

with nature and become so alienated from

the earth in our industrial, technological,

urbanized society. We are no longer natural

and spontaneous “earthy mystics”

like the ancient Jews, Jesus, and the early

Christian saints. Gardening, for example,

should be an instinct like praying, dancing,

or making love. But we’ve lost the

knack in our dehumanized, derivative, indoor

existence, and need to rely on “how-to”

books of techniques.

At the coming of spring, the Pueblo Indian covers himself with earth. On the first day of Lent, the Judeo-Christian blackens his forehead with ashes and hears the words, “Remember that you are dust and to dust you will return.” In each case, intimacy with the earth is the meaning of the act. We are intimately related to the earth because we are made out of the very stuff of it. Genesis teaches us that God formed us out of the dust of the ground and to this earth will return us (Gen. 2:7, 3:19). While the earthy Native American mystic says: “I must go into the earth itself/to know the source from which I came,” the earthy Judeo-Christian mystic sings “I give you thanks that I am fearfully, wonderfully made… in secret… fashioned in the depths of the earth” (Psalm 138).

Tessa and Fr. Dave Denny Composting in

Nova Scotia, 1970s

Man or Worm?

The Book of Job is a superb example of

Judeo-Christian earthiness. The final chapters

provide some of the most ecstatic, earthy

lyricism in biblical literature (see Job

36:26-42:6). But the bulk of the book is

characterized by a more appropriate “Lenten

lyricism.” Job sits on a dung heap,

a great source of wisdom, as anyone who

has shoveled manure mindfully will tell

you, and reflects on the human condition.

Job says: “I am leveled with the

dust and ashes. He has cast me into the

mire” (30:19). “Man, born of

woman, is… like a flower that blossoms

and withers… he wastes away like

a rotten thing” (19:1-2, 13:28).

“Man is but a maggot, the son of

man only a worm” (25:6). This outlook

on life echoes Psalm 22 which plays an

important part in the liturgy of Lent,

especially at the stripping of the altar

on Holy Thursday and on Good Friday: “…to

the dust of death you have brought me down…

I am a worm, not a man.”

Researchers have estimated that there are 50,000 earthworms per acre of land. That many worms annually bring 36,000 pounds of subsoil to the surface as worm castings on each acre. Within twenty years, these castings add three inches of new soil to that same acre of earth. Reading facts like this can make a man glad to be a worm!

Our “worminess” is not only an important scriptural theme; it also figures significantly in the writings of Carmelite mystic, Teresa of Avila. Throughout her major work, The Interior Castle, Teresa refers to humanity as an ugly worm (5:2:7), a foul-smelling worm (1:1:3), and a worm with such limited powers that we cannot understand the grandeurs of God (6:47). Teresa seems to have had a highly refined olfactory sense experience of God whom she often found fragrant and sweet-smelling.

Her visions of hell, sin, and the devil, on the other hand, were foul-smelling and malodorous. In her Way of Perfection, Teresa even thanked God for the “bad odor He must endure” in allowing her to get near him (22:4)! This is the same mystical sensitivity that led the author of the Cloud of Unknowing to call himself “a stinking lump of sin” and a humble little boy in our own era to pray, “O Lord, my name is mud!”

In her use of worm imagery, Teresa was not a very good naturalist, since worms are not usually smelly! But she was a good theologian and a fine metaphysician in her recognition of our “wormhood” in the face of divine majesty. Her approach is graphically feminine, beginning with the raw material of everyday existence.

These examples are no more “negative” than Christ himself in his own Gospel view of the human condition: Unless you humble yourself you cannot be exalted (Mt. 23:12); unless you lose your life you cannot find it (John 12:25); unless you make yourself last you cannot be first (Mark 9:36).

Teresa’s “worm talk” is not popular in our egotistical age, characterized by glorification of the self. But only when we recognize our nothingness, our worminess, our muddiness, can we rise to our full human stature. As we pray in Psalm 8: “Who are we that you should care for us? You have made us little less than a god and covered us with glory and honor.”

Composting in Colorado, 1980s

Compost

Another inspiration for Lent is an old

article from National Geographic

entitled “The Wild World of Compost.”

The author is a professor of natural history

from California. The photographer built

a compost pile in her own back yard in

order to capture the proper pictures. Together

they demonstrate how the compost pit is

a perfect meditation for Lent, the essence

of spring as well: “new life from

old.” To return to our Pueblo Indians:

compost, like Lent and spring, “contains

all previous births and deaths.”

The author-professor is contemplative. Like a good Native American or an earthy Judeo-Christian mystic, he sees with his poetic inner eye as well as his scientific outer eye. Sow bugs are “gray galleons;” springtails are “jumping jacks;” and worms are “silent, subterranean contractors… the unsung heroes of the world beneath our feet.” Watching a millipede crawl slowly, softly over decaying humus, he sings exultantly, is like “watching a symphony in movement.” He is obviously enchanted by the earthly alchemy of compost, just like Walt Whitman, whom he quotes: “Behold this compost! Behold it well…! It grows such sweet things out of such corruptions.” As Job observed on his dung heap, “I must call corruption ‘my father’ and the maggot ‘my mother’” (17:14).

We must not relegate the reality of compost to our manual labor and divorce it from our prayer and contemplation. We cannot separate body and soul, matter and spirit, earth and heaven. According to Hugh L’Anson Fausset, a contemporary European writer, “the dependence of growth on decomposition in the physical world” relates intimately to “the processes of the spiritual world.” For “the more we study the chemistry of the body, the more kindred it appears to the chemistry of the soul.”

Metanoia

in the Garden

The more we study the springtime alchemy

of the earth, the more kindred it appears

to the Lenten metanoia of our

hearts. Metanoia, radical conversion

of mind and heart, is the whole meaning

of Lent. On Ash Wednesday, St. Paul tells

us to be reconciled to God (2 Cor. 5:20).

The prophet Joel urges us to return to

God with all our hearts, “fasting,

weeping, mourning.” “Rend your

hearts, not your garments,” he says

(2:12-113). Psalm 51 explains that our

Lenten sacrifice must be a humble contrite

heart. Ultimately that is the purpose of

Lent, the meaning of all our sacrifice

and self-denial, our fasting and penance,

our asceticism and Lenten discipline: humility

of heart.

According to Gerald Vann, the British Dominican, “We shall form quite a wrong picture of Lenten sacrifice if we think of it in terms of striding purposefully, self-assured, head thrown well back towards a greater mastery, a more thorough domination over the materials of life. We shall be far safer sitting down quietly on the grass, humbly accepting… the ultimate facts about God and man.”

How simple, then, we can make our Lent: to sit down on the grass with the followers of Jesus before he multiplied the loaves (John 6:10); to sit in the dung heap humbly with Job; to “touch the yielding earth” with the Pueblo Indians; in a word, to spend Lent in the garden.

There is more wisdom to be gleaned in the garden than anywhere else on earth. No wonder Jesus used the garden so often in his teachings: the parable of the sower (Mt. 13:4), the mustard seed (Mt. 13:31), the wheat and weeds (Mt. 13:24); the images of the seed growing by itself (Mark 4:26), the lilies of the field (Mt. 6:28), the grains of wheat (John 12:24). As Blaise Pascal wrote in the 17th century, “We were lost and saved in a garden. We began our life in the garden of Eden. Our redemption was assured in the garden of Gethsemane.” When God feels absent, we thirst like Jesus on the Cross and long for God, “like a dry weary land without water” (Psalm 63). And when we feel God present, we feel “like a garden well-watered” (Jer. 31:12).

Humility of Heart

Humility of heart is the meaning behind

all our Lenten discipline. And we learn

humility from every aspect of our springtime

gardening. In communion with fruit trees

and rosebushes we are pruned: “I

am the vine, and my Father is the vinedresser.

Every branch that bears no fruit he cuts

away, and every branch that does bear fruit

he prunes to make it bear even more”

(John 15:1-2).

In union with manure and compost, we die in order to make humus, the dark, rich, fertile ground that flowers “with life born of ancient death.” (The very word “humility” comes from the Latin word “humus.”) And in harmony with the furrows waiting to be planted, we, too, lie fallow, barren, empty, waiting for Easter and “the birth of what is innocent and green.”

Composting seaweed in Ireland, 1995; Composting

“smarter” in Colorado, 2008