![]()

Voice of the Desert

Tessa Bielecki

Art by Catherine LePoutre

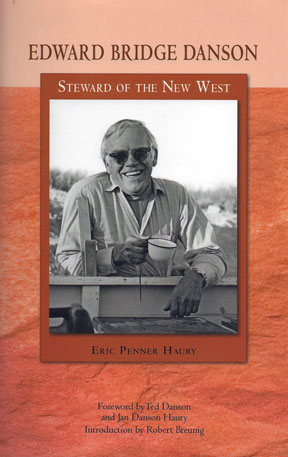

A Response to Edward Bridge Danson: Steward of the West,

by Eric Penner Haury

Hardcover: Museum of Northern Arizona, 2011

Book cover

Instead of a formal review of Steward of the West by Ned Danson’s grandson, I opted for a more imaginative “interview” with my old friend in the present tense. All the questions are in my own voice. Ned’s responses are taken accurately from Haury’s book with the exceptions of Jess’s 80th birthday, my move to Sedona, and the tale of my living in Juliana hermitage.

A shorter version of this “interview” appeared in our Winter 2013 Caravans newsletter. The “web-only” paragraphs appear below in green.

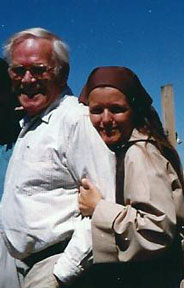

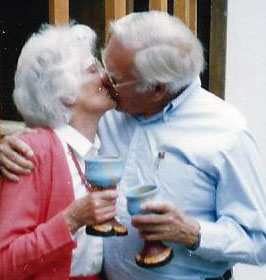

Ned with Tessa at Nada Hermitage in Colorado.

Tessa: Ned, even though we both were born and raised in the lush green east, you and I share a passion for the arid Arizona desert. When did your love affair with the desert begin?

Ned: I first saw Arizona in 1926 when my family traveled to the Southwest from Cincinnati. My memories of that trip are faint, yet I recall the Grand Canyon, Indian dances, and visits to various archeological sites. But at age ten, I was more interested in the big cars we drove!

T: That changed on your second visit to the desert?

N: In 1937, at age 21, I drove to Arizona to help my uncle turn some desert land south of Tucson into a dude ranch. As we drove out of the canyon west of Bisbee and up on to the plateau to Tombstone at 5 am, there was a pink and blue pre-sunrise sky with fleecy white clouds, a hill with a coyote on it – I know it’s melodramatic, but that’s the way it was. I fell in love with Arizona there and knew it was going to be my home.

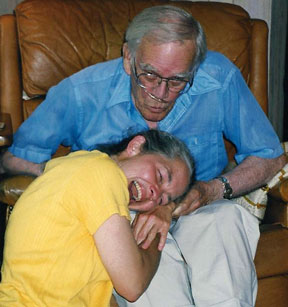

David Levin clowns around with Ned in Nova Scotia

T: Arizona was even part of your “marriage proposal” to Jessica, right?

N: On our first date I said, “You’re going to love Arizona.” She thought, “Wow, what a line!” I wasn’t engaged for a while, but doing my darndest to be. My only worry was whether Jess would like Arizona and like going on expeditions and roughing it. She’d “camped out,” but never “lived out.” There’s a big, big difference. But she loved the open. She was a good sport with a sense of humor. And she had imagination and intelligent interest, all necessary attributes.

T: And did she fall in love with the Arizona desert, too?

N: She did. We were married in 1942. After serving in World War II as a naval ensign, we bought a house in Tucson in 1945. Then I got my PhD in Anthropology at Harvard. For my dissertation, I surveyed the Upper Gila River Basin, 14,500 square miles of wilderness along the Arizona-New Mexico border. For three summers, while Jess lived in California with her parents and our two children, I filled in the archeological map. I taught briefly at the University of Colorado in Boulder where I felt I should get excited by Plains archeology. But I never did. The Southwest was always my cup of tea. In 1950 I was asked to teach at the U of A in Tucson, and we moved onto five acres of Sonoran desert. With few houses nearby, we could look out on the desert and walk there whenever we wanted. Our son Ted developed a passion for horseback riding. Our daughter Jan loved playing “knights” with long, straight “ribs” of dead saguaro cactus as lances. Jessica loved wild nature and thrilled to Arizona’s powerful thunderstorms. One day she heard thunder crashing outside, threw open the door, and called out, “Isn’t this glorious?”

Fr. Dave and Jessica share a laugh in the library.

T: She didn’t like moving to Flagstaff in northern Arizona?

N: Not at first. I joined the Board of Trustees of the Museum of Northern Arizona in 1953. In 1956 the Museum needed a new assistant director. Jessica asked who should be named, and I was suggested. For years she considered asking the question one of her worst mistakes. I served as assistant director from 1956-1958 and then director from 1959-1975. Jessica and I especially loved the annual Hopi Show which stimulated a market for the tribe’s arts and crafts so that their traditional skills would not be lost – pottery, jewelry, rugs, baskets, katsina dolls.

T: There was a Navajo show, too, but you and Jessica were closer to the Hopi?

N: Over the years we developed a network of friendships and partnerships with the Hopi. We attended their dances on Saturdays with the same reverence we brought to the Episcopal Church on Sundays. Before each Hopi show, Jess and I and other members of the Museum went from village to village, house to house to collect items for the annual exhibit. People welcomed us warmly into their homes on the desert mesas. You should have heard them laugh when I stumbled through the few Hopi words I’d managed to learn! I was something of a tease, which stood me in good stead with many Hopi women who could give great teases back!

Ned and Jessica renew their wedding vows at Nada.

T: Jessica played a big part in your work, didn’t she?

N: She typed up everything I wrote for my dissertation, and we edited it together. As well as entertaining guests from the Museum, Jessica cleaned cabins for summer assistants and took care of sick staff. As one student wrote years later, “Jessica was an essential presence, providing a depth and beauty of character and spirit that nourished” us all. I was energized by the entertaining and loved playing host. But it began to drain Jessica. You know how she loved her solitude. Yet she felt bound to give hospitality – both by a sense of duty and her own inborn desire to give of herself.

T: Which brings us to Sedona, where we met.

N: All the entertaining got harder for Jessica. In one year alone, we had 500 guests. When they stayed overnight, Jessica missed her solitude in the tiny chapel she’d created in the house. Without this quiet time, she felt her life was out of balance. In 1969 her sister moved to Sedona and Jess started to visit her. Since you moved to Sedona yourself in 1967 to join the Spiritual Life Institute, you remember how small the town was then, with only 2700 residents. In 1971, Jessica discovered “Singing Waters,” and soon after we bought the house with its beautiful gardens, apple orchard, and frontage on Oak Creek.

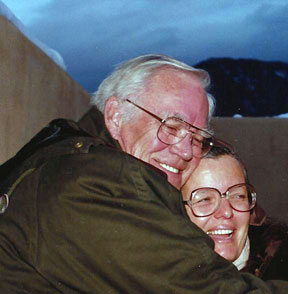

Ned and Tessa on a cold Colorado evening.

T: Getting to know you and Jessica during those years remains one of the highlights of my life.

N: Jessica found SLI’s contemplative Christianity invigorating and became such an eager friend of all you “Nadans,” as she loved to call you. I wasn’t initially drawn to your community. At first I resisted, but as I got to know you all, I changed my thinking – changed it completely.

T: At the end of your life, did you experience the “desert of human diminishment?”

N: My health started to decline. Decades of smoking gave me emphysema and heart problems. I had a hard time giving up cigarettes and even deceived Jessica about quitting. And my memory was fading. I could easily use my charm and social skills to cover up my growing forgetfulness, but details were starting to slip. In 1974, the Board of Trustees and I decided it was time for me to retire as director of the Museum.

Jessica and Tessa converse at Jessica’s Sedona home.

T: But you stayed involved for almost 25 more years.

N: After retirement I became President of the Board of Trustees and continued to use my skills to help the Museum without having to deal with day-to-day details. Jessica and I made plans to move to Sedona full time and designed an extra wing to turn Singing Waters into a year-round house. It became a living reliquary of our lives. We covered the floors with Navajo rugs, built a special shelf for our Hopi pots and baskets, and hung the walls with Jeffrey Lungé’s Southwest paintings. And we added a small chapel for Jessica, where you also came to pray with us.

T: You also operated on a much wider stage throughout the region, influencing federal policies and initiatives in Arizona and the West almost until your death.

N: Yes, bear with me as I give you a more formal list. In 1958 Senator Barry Goldwater recommended me for the archeologist’s seat on the National Park Service Advisory Council where I served until its demise in the early 1980s. My service on the Southwest Parks and Monuments Association Board continued until 1986. When I left, SPMA established the Edward B. Danson Distinguished Associate Award “for contributions to greater public understanding of the importance of the National Parks.”

I helped establish Canyonlands National Park in 1964. At the Museum we did “salvage archeology” in the Glen Canyon area of Arizona, recording prehistoric sites and petroglyphs before Lake Powell flooded the area when the Glen Canyon dam was built.

In 1965 I testified before Congress, and President Johnson signed a bill making Hubbell Trading Post a National Historic Site because of its critical role in the history of Arizona and the Navajo people. I’d worked on the project since 1957, so I considered this one of my greatest accomplishments.

In 1970 I sent out more than 100 invitations to various groups and helped create CPEAC, the Colorado Plateau Environmental Advisory Council. We were increasingly concerned about the dilemmas of dams, air pollution from coal mining, and the pumping of massive quantities of water out of the main aquifer on Navajo-Hopi desert lands.

The capstone of my career came in 1986 when the Department of the Interior gave me its Conservation Award for “more than thirty years of deep commitment and efforts towards the preservation of natural and cultural resources.”

My nephew, Dan Perrin, established the Edward B. Danson, Jr. Endowed Chair of Anthropology at the Museum of Northern Arizona in 1991. [Steward of the West was written to help fund this chair.]

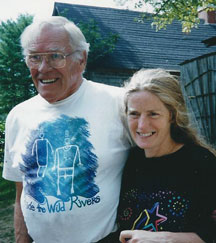

Ned and Jessica at Juliana Hermitage.

T: But you couldn’t “save” Sedona, however, and that forced us to move the SLI to Colorado.

N: Like you, I felt strongly that the loss of Sedona’s scenic area would be a loss for all Americans. With other Sedonans, I tried to make part of Sedona a National Park, but failed. So I joined Keep Sedona Beautiful, and in the 1980s we “saved” three national wilderness areas near Sedona. But I didn’t save the land around SLI, so Arizona lost you to Colorado.

T: Despite the distance, we remained close friends.

N: Yes, we loved our regular visits to Crestone, and loved building Juliana, the first hermitage for you there. I love how it reminded you of our Sedona home. And I’m glad you got to “christen” it and live there for several months, alone at the new Nada, while the chapel and other hermitages were being built. It was deeply meaningful for Jess and me, members of the Episcopal Church since birth, to convert to Roman Catholicism under SLI’s influence, and renew our wedding vows with you in Colorado. And we celebrated Jess’s 80th birthday there, too.

T: Among life’s many rewards and awards, you also suffered increasing diminishment.

N: In 1987 I had a heart attack. By 1994, Jessica noticed that my memory was seriously failing. That year I fell and suffered a back injury that never fully healed. After I broke my ribs falling into the irrigation ditch at Singing Waters, I required supplemental oxygen full time. I could still tell tales from my youth, yet I had difficulty recalling what happened that very day. And I loved the southwestern desert until the day I died.

Shortly before his death, Ned leans down to kiss his friend Connie Bielecki.

Postscript

Ned Danson died on November 30, 2000. I last saw him only two months before when I slept outside Singing Waters under a huge cottonwood tree, watching the desert stars as an owl hooted over the rose garden Ned had tended so lovingly. The entire SLI community was there. Knowing that both Ned and Jessica were nearing the end of their lives, we “anointed” them in a moving outdoor ceremony.

I remember Ned as a big barrel-chested bear of a man with a generous heart and a hearty laugh. So do his old friends, Ray and Molly Thompson, who wrote:

“No one could pack so much meaning into a laugh as Ned Danson. Whether it was a quiet chuckle or a hearty guffaw, his laugh injected something special into any and every situation. His laughter could be quietly cheerful, enthusiastically joyful, raucously lecherous, mischievously silly, properly stern, [or] unconsciously cynical…. He was as eager to laugh ‘when the joke was on him,’ as when it was not…. His laughter was one of the strong suits in his unique kind of social interaction that enabled him to accomplish so much….”

Jessica died five years after Ned on January 11, 2006. Thanks to her daughter, Jan Haury, I had the privilege of sitting with Jessica for the ten days of her dying. You may read my account of this profound “desert experience” here.

Although Ned did not live through the enormous changes that took place in the SLI after 2003, Jessica did. She witnessed the creation of the Desert Foundation and blessed our efforts to explore the wisdom of the world’s deserts. In many ways, the Desert Foundation carries on the Dansons’ legacy as “stewards” of the desert.

The year before she died, from January through September 2005, Jessica wrote us these words of encouragement: “Dear Fr. Dave and Tessa, You both are such a breath of fresh air and such an inspiration and nourishment for my soul, it is always hard to say goodbye to you. You live so fully – it delights me…. I think your discernment in leaving SLI is a very wise choice and the only way for you to go. I’m excited about the future for both of you. You are so dear and thoughtful to keep us posted on your new Desert Foundation. We are thrilled to hear how everything has unfolded so beautifully.”

Tessa joins Eric Penner Haury, author of Edward Bridge Danson: Steward of the West, Ted Danson, Jan Danson Haury, and Mary Steenburgen, to raise funds in Flagstaff for the Ned Danson Chair of Anthropology. To order copies of the book, contact the Museum of Northern Arizona bookstore http://shops.musnaz.org/. All proceeds help support the Ned Danson Chair.

Ned with Sharon Doyle at Nova Nada in Nova Scotia.